Handling missing values is one of the worst nightmares a data analyst dreams of. In situations, a wise analyst ‘imputes’ the missing values instead of dropping them from the data.

Missing Data in Analysis

At times while working on data, one may come across missing values which can potentially lead a model astray. Handling missing values is one of the worst nightmares a data analyst dreams of. If the dataset is very large and the number of missing values in the data are very small (typically less than 5% as the case may be), the values can be ignored and analysis can be performed on the rest of the data. Sometimes, the number of values are too large. However, in situations, a wise analyst ‘imputes’ the missing values instead of dropping them from the data.

What Are Missing Values

Think of a scenario when you are collecting a survey data where volunteers fill their personal details in a form. For someone who is married, one’s marital status will be ‘married’ and one will be able to fill the name of one’s spouse and children (if any). For those who are unmarried, their marital status will be ‘unmarried’ or ‘single’.

At this point the name of their spouse and children will be missing values because they will leave those fields blank. This is just one genuine case. There can be cases as simple as someone simply forgetting to note down values in the relevant fields or as complex as wrong values filled in (such as a name in place of date of birth or negative age). There are so many types of missing values that we first need to find out which class of missing values we are dealing with.

Types of Missing Values

Missing values are typically classified into three types – MCAR, MAR, and NMAR.

MCAR stands for Missing Completely At Random and is the rarest type of missing values when there is no cause to the missingness. In other words, the missing values are unrelated to any feature, just as the name suggests.

MAR stands for Missing At Random and implies that the values which are missing can be completely explained by the data we already have. For example, there may be a case that Males are less likely to fill a survey related to depression regardless of how depressed they are. Categorizing missing values as MAR actually comes from making an assumption about the data and there is no way to prove whether the missing values are MAR. Whenever the missing values are categorized as MAR or MCAR and are too large in number then they can be safely ignored.

If the missing values are not MAR or MCAR then they fall into the third category of missing values known as Not Missing At Random, otherwise abbreviated as NMAR. The first example being talked about here is NMAR category of data. The fact that a person’s spouse name is missing can mean that the person is either not married or the person did not fill the name willingly. Thus, the value is missing not out of randomness and we may or may not know which case the person lies in. Who knows, the marital status of the person may also be missing!

If the analyst makes the mistake of ignoring all the data with spouse name missing he may end up analyzing only on data containing married people and lead to insights which are not completely useful as they do not represent the entire population. Hence, NMAR values necessarily need to be dealt with.

Imputing Missing Values

Data without missing values can be summarized by some statistical measures such as mean and variance. Hence, one of the easiest ways to fill or ‘impute’ missing values is to fill them in such a way that some of these measures do not change. For numerical data, one can impute with the mean of the data so that the overall mean does not change.

In this process, however, the variance decreases and changes. In some cases such as in time series, one takes a moving window and replaces missing values with the mean of all existing values in that window. This method is also known as method of moving averages.

For non-numerical data, ‘imputing’ with mode is a common choice. Had we predict the likely value for non-numerical data, we will naturally predict the value which occurs most of the time (which is the mode) and is simple to impute.

In some cases, the values are imputed with zeros or very large values so that they can be differentiated from the rest of the data. Similarly, imputing a missing value with something that falls outside the range of values is also a choice.

An example for this will be imputing age with -1 so that it can be treated separately. However, these are used just for quick analysis. For models which are meant to generate business insights, missing values need to be taken care of in reasonable ways. This will also help one in filling with more reasonable data to train models.

More R Packages for Missing Values

In R, there are a lot of packages available for imputing missing values – the popular ones being Hmisc, missForest, Amelia and mice. The mice package which is an abbreviation for Multivariate Imputations via Chained Equations is one of the fastest and probably a gold standard for imputing values. Let us look at how it works in R.

Using the mice Package – Dos and Don’ts

The mice package in R is used to impute MAR values only. As the name suggests, mice uses multivariate imputations to estimate the missing values. Using multiple imputations helps in resolving the uncertainty for the missingness.

The package provides four different methods to impute values with the default model being linear regression for continuous variables and logistic regression for categorical variables. The idea is simple!

If any variable contains missing values, the package regresses it over the other variables and predicts the missing values. Some of the available models in mice package are:

- PMM (Predictive Mean Matching) – suitable for numeric variables

- logreg(Logistic Regression) – suitable for categorical variables with 2 levels

- polyreg(Bayesian polytomous regression) – suitable for categorical variables with more than or equal to two levels

- Proportional odds model – suitable for ordered categorical variables with more than or equal to two levels

In R, I will use the NHANES dataset (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data by the US National Center for Health Statistics). We first load the required libraries for the session:

#Loading the mice package library(mice) #Loading the following package for looking at the missing values library(VIM) library(lattice) data(nhanes)

The NHANES data is a small dataset of 25 observations, each having 4 features – age, bmi, hypertension status and cholesterol level. Let’s see how the data looks like:

# First look at the data str(nhanes) 'data.frame': 25 obs. of 4 variables: $ age: num 1 2 1 3 1 3 1 1 2 2 ... $ bmi: num NA 22.7 NA NA 20.4 NA 22.5 30.1 22 NA ... $ hyp: num NA 1 1 NA 1 NA 1 1 1 NA ... $ chl: num NA 187 187 NA 113 184 118 187 238 NA ...

The str function shows us that bmi, hyp and chl has NA values which means missing values. The age variable does not happen to have any missing values. The age values are only 1, 2 and 3 which indicate the age bands 20-39, 40-59 and 60+ respectively. These values are better represented as factors rather than numeric. Let’s convert them:

#Convert Age to factor nhanes$age=as.factor(nhanes$age)

It’s time to get our hands dirty. Let’s observe the missing values in the data first. The mice package provides a function md.pattern() for this:

#understand the missing value pattern

md.pattern(nhanes)

age hyp bmi chl

13 1 1 1 1 0

1 1 1 0 1 1

3 1 1 1 0 1

1 1 0 0 1 2

7 1 0 0 0 3

0 8 9 10 27

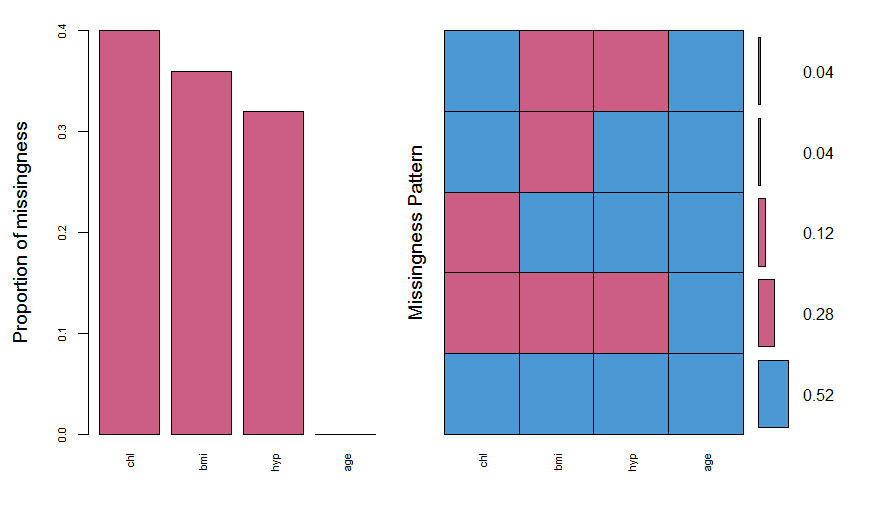

The output can be understood as follows. 1’s and 0’s under each variable represent their presence and missing state respectively. The numbers before the first variable (13,1,3,1,7 here) represent the number of rows. For example, there are 3 cases where chl is missing and all other values are present. Similarly, there are 7 cases where we only have age variable and all others are missing. In this way, there are 5 different missingness patterns. The VIM package is a very useful package to visualize these missing values.

#plot the missing values

nhanes_miss = aggr(nhanes, col=mdc(1:2), numbers=TRUE, sortVars=TRUE, labels=names(nhanes), cex.axis=.7, gap=3, ylab=c("Proportion of missingness","Missingness Pattern"))

We see that the variables have missing values from 30-40%. It also shows the different types of missing patterns and their ratios. The next thing is to draw a margin plot which is also part of VIM package.

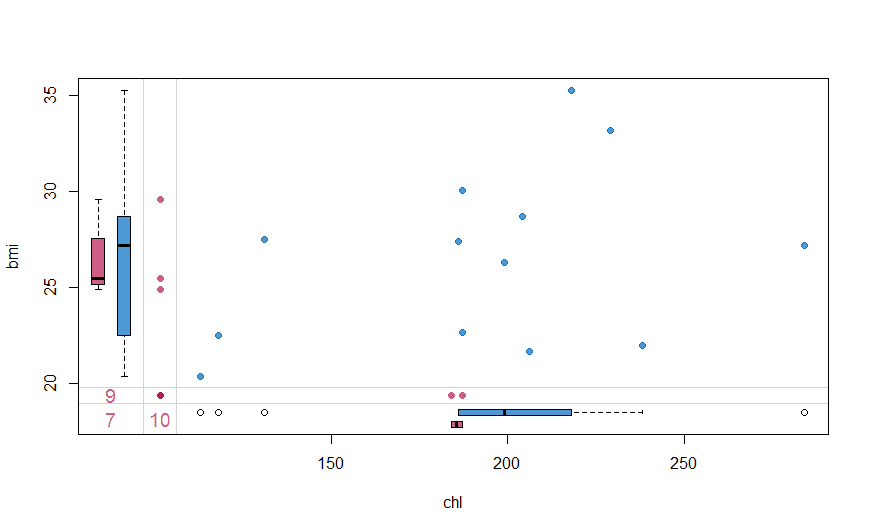

#Drawing margin plot

marginplot(nhanes[, c("chl", "bmi")], col = mdc(1:2), cex.numbers = 1.2, pch = 19)

The margin plot, plots two features at a time. The red plot indicates distribution of one feature when it is missing while the blue box is the distribution of all others when the feature is present. This plot is useful to understand if the missing values are MCAR. For MCAR values, the red and blue boxes will be identical.

Let’s try to apply mice package and impute the chl values:

#Imputing missing values using mice

mice_imputes = mice(nhanes, m=5, maxit = 40)

I have used three parameters for the package. The first is the dataset, the second is the number of times the model should run. I have used the default value of 5 here. This means that I now have 5 imputed datasets. Every dataset was created after a maximum of 40 iterations which is indicated by “maxit” parameter.

Let’s see the methods used for imputing:

#What methods were used for imputing mice_imputes$method age bmi hyp chl "" "pmm" "pmm" "pmm"

Since all the variables were numeric, the package used pmm for all features. Let’s look at our imputed values for chl

1 2 3 4 5 1 187 118 238 187 187 4 186 204 218 199 204 10 187 186 199 204 284 11 131 131 199 238 199 12 131 187 229 204 186 15 131 238 187 187 187 16 118 199 118 131 187 20 206 184 184 218 229 21 131 118 113 113 131 24 199 218 206 218 206

We have 10 missing values in row numbers indicated by the first column. The next five columns show the imputed values. In our missing data, we have to decide which dataset to use to fill missing values. This is then passed to complete() function. I will impute the missing values from the fifth dataset in this example

#Imputed dataset Imputed_data=complete(mice_imputes,5)

Goodness of fit

The values are imputed but how good were they? The xyplot() and densityplot() functions come into picture and help us verify our imputations

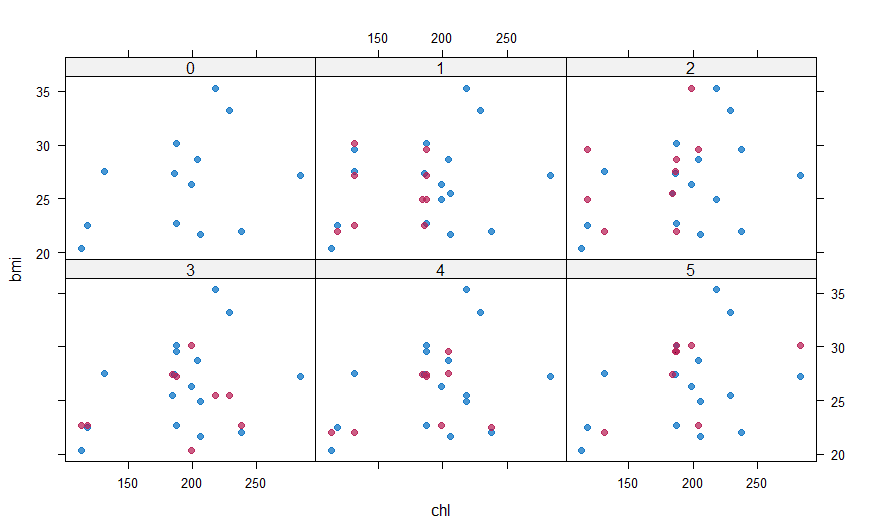

#Plotting and comparing values with xyplot() xyplot(mice_imputes, bmi ~ chl | .imp, pch = 20, cex = 1.4)

Here again, the blue ones are the observed data and red ones are imputed data. The red points should ideally be similar to the blue ones so that the imputed values are similar. We can also look at the density plot of the data.

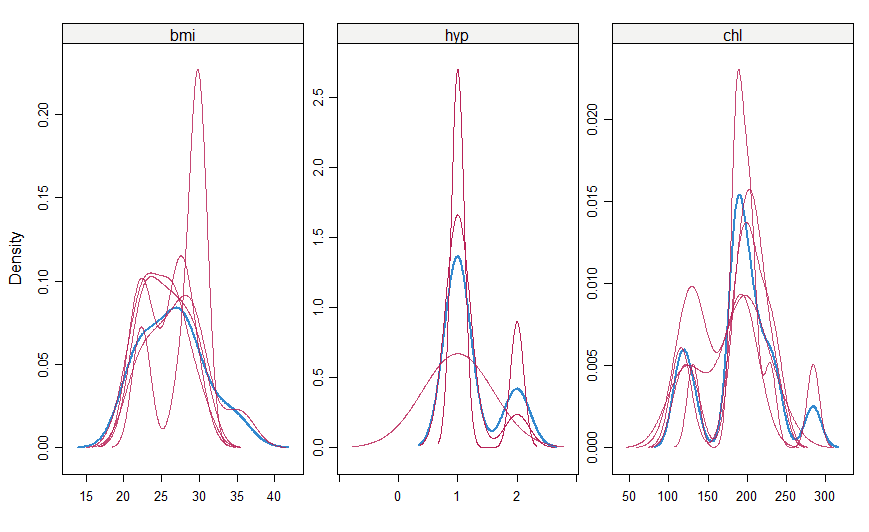

#make a density plot densityplot(mice_imputes)

Just as it was for the xyplot(), the red imputed values should be similar to the blue imputed values for them to be MAR here.

Summary – Modelling with mice

Imputing missing values is just the starting step in data processing. Using the mice package, I created 5 imputed datasets but used only one to fill the missing values. Since all of them were imputed differently, a robust model can be developed if one uses all the five imputed datasets for modelling. With this in mind, I can use two functions – with() and pool().

The with() function can be used to fit a model on all the datasets just as in the following example of linear model

#fit a linear model on all datasets together lm_5_model=with(mice_imputes,lm(chl~age+bmi+hyp)) #Use the pool() function to combine the results of all the models combo_5_model=pool(lm_5_model)

The mice package is a very fast and useful package for imputing missing values. It can impute almost any type of data and do it multiple times to provide robustness. We can also use with() and pool() functions which are helpful in modelling over all the imputed datasets together, making this package pack a punch for dealing with MAR values.